20 Dec 2024

This study aims to analyze the effect of small changes in crank length on the biomechanics of submaximal pedaling. The fundamental hypothesis was that a shorter crank could allow a lower trunk position and changes to the lower extremities position from an aerodynamic point of view as well as the kinematics and kinetics from a biomechanic perspective. It is meant to complement our theoretical study to evaluate the aerodynamic consequences of changing the posture on a road racing bicycle derived by a shorter crank, Decreased drag with shorter crank length.

To evaluate the adaptation and changes resulting from using a shorter crank in high-level cyclists during submaximal pedaling when combined with a more aerodynamic position, seven young elite cyclists were recruited during their winter training period and asked to change their cycling setup with the goal of improving their performance. None of them had recently had hip, knee or ankle joint injuries or pain, so their main concern was not assuming a more comfortable and/or safer posture, which is considered a common reason to use shorter cranks in order to reduce the range of motion of the lower extremities joints, but improving their skills/efficiency. We decided not to compare our results with the published research on similar aspects of position since none of them adopted a combined scenario on the implications on biomechanics of the lower extremities due to a combined effect of crank length and aerodynamic posture but only one aspect. Cyclists, when using a shorter crank arm, need to increase the average useful force or the average cadence or a combination of the two parameters to maintain the same power output. We assumed that the choice would favor an increase in cadence in order to maintain a similar pedal speed (crank angular velocity * crank length) to that of the standard crank.

The data for this study were collected from seven young elite competitive cyclists (5 males and 2 females), mean age 23.3 years (SD 1.9 yrs), mean weight 67.1 kg (SD 1.9 kg), mean height 1.73 m (SD 0.05 m). They were using a standard length crank (4 cyclists 172.5 mm and 3 cyclists 175 mm) and all were asked to switch to a 165 mm crank. Table 1 details general cyclist data as well as the crank lengths, pedaling rates, and pedal speeds used in both experimental conditions.

| Cyclist | Height (m) |

Weight (kg) | Age (yrs) |

Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclist 1 | 1.78 | 67 | 23 | male |

| Cyclist 2 | 1.69 | 69 | 25 | female |

| Cyclist 3 | 1.73 | 64 | 21 | male |

| Cyclist 4 | 1.80 | 68 | 24 | male |

| Cyclist 5 | 1.70 | 67 | 20 | female |

| Cyclist 6 | 1.75 | 70 | 26 | male |

| Cyclist 7 | 1.76 | 65 | 24 | male |

Each cyclist used his bicycle mounted on a magnetic freewheel trainer to keep his standard setup. The seat position was modified to preserve the leg's position at its maximum extension in the crank cycle (approximately 165 degrees from the top dead center - TDC). As a consequence of the shorter crank arm, the hip joint was less flexed transitioning over the TDC and this allowed cyclists to assume a lower trunk posture. To mantain the position of the leg at maximum extension unchanged, each cyclist moved the saddle up and slightly to the rear, keeping the same seat post angle. The height and posterior/anterior position of the handlebars were maintained between the two testings conditions, and cyclists were asked to keep their hands on the hoods.

| Cyclist | Original crank length (mm) | Final crank length (mm) | Original cadence (rpm) | Final cadence (rpm) | Original pedal speed (m/s) | Final pedal speed (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclist 1 | 172.5 | 165 | 90 | 92 | 1.62 | 1.59 |

| Cyclist 2 | 172.5 | 165 | 90 | 95 | 1.62 | 1.64 |

| Cyclist 3 | 175 | 165 | 90 | 92 | 1.65 | 1.59 |

| Cyclist 4 | 175 | 165 | 90 | 95.2 | 1.65 | 1.64 |

| Cyclist 5 | 172.5 | 165 | 90 | 94.4 | 1.62 | 1.63 |

| Cyclist 6 | 172.5 | 165 | 90 | 93 | 1.62 | 1.60 |

| Cyclist 7 | 175 | 165 | 90 | 95.6 | 1.65 | 1.65 |

All participants were analyzed in the laboratory during two sessions spaced six weeks apart. During the first meeting, data were collected with the habitual crank each cyclist was using and all cyclists were asked to pedal at an average power of 240 W and a fixed cadence of 90rpm which was maintained using a metronome and visual feedback from the power meter. The desired power output was obtained by adjusting the gears such that the average power output reading was equal to the desired power. The following 6-week period was used to get accustomed (on average, 6 training sessions and 400 km weekly) to the shorter crank. During these weeks, they were asked to focus on a more aerodynamic lowered position, to be acquired gradually. To facilitate this adaptation, twice a week sessions of stretching of the posterior muscle chain (back and lower limbs) and strengthening of the core muscles, particularly those of the pelvis, were included. In the second session in the laboratory, each cyclist was asked to pedal at an imposed power output (240 W), assume the new aerodynamic position, and pedal at a cadence that they felt replicated the same perceived effort as in the previous session.

Data were collected for three minutes of seated cycling. To track kinematics, 40 retroreflective markers were applied to the cyclist body and four markers were placed on each pedal and sampled at 125 Hz with 8 infrared cameras. Synchronous pedal bidirectional reaction forces were collected at 500 Hz with a custom instrumented pedal. Marker data were filtered with a second-order low-pass dual-pass Butterworth 6 Hz filter and pedal reaction force data were filtered with a low-pass 10 Hz filter (R Foundation, https://www.r-project.org). All computational simulations were performed in OpenSim (v.4.5; https://simtk.org/projects/opensim; Delp et al., 2007). For each participant, marker data recorded during the calibration trials were used to generate a subject-specific musculoskeletal model: the scaling tool used measurement-based scaling factors, obtained from the difference between the experimental and model markers of the static trial of the participant, to vary the mass and inertial properties as well as dimensions of the body segments. A 6-degree-of-freedom (dof) pelvis was the base segment, and each lower limb included a 3-dof hip, a 1-dof knee, with translations and nonsagittal rotations obtained as a function of knee flexion and a 2-dof ankle. The metatarsophalangeal joint was blocked to simulated the rigid shoe/pedal interface.

The scaled models were then used to compute joint angles and net joint torques around each dof using inverse kinematic and inverse dynamic tools, respectively. For each cycling trial, data were interpolated and then averaged across 10 successive crank cycles, where the average cadence of the riders had a variance < 1 rpm across the 10 cycles. The start and end of each crank cycle were defined as the position at which the right crank was aligned with the vertical axis.

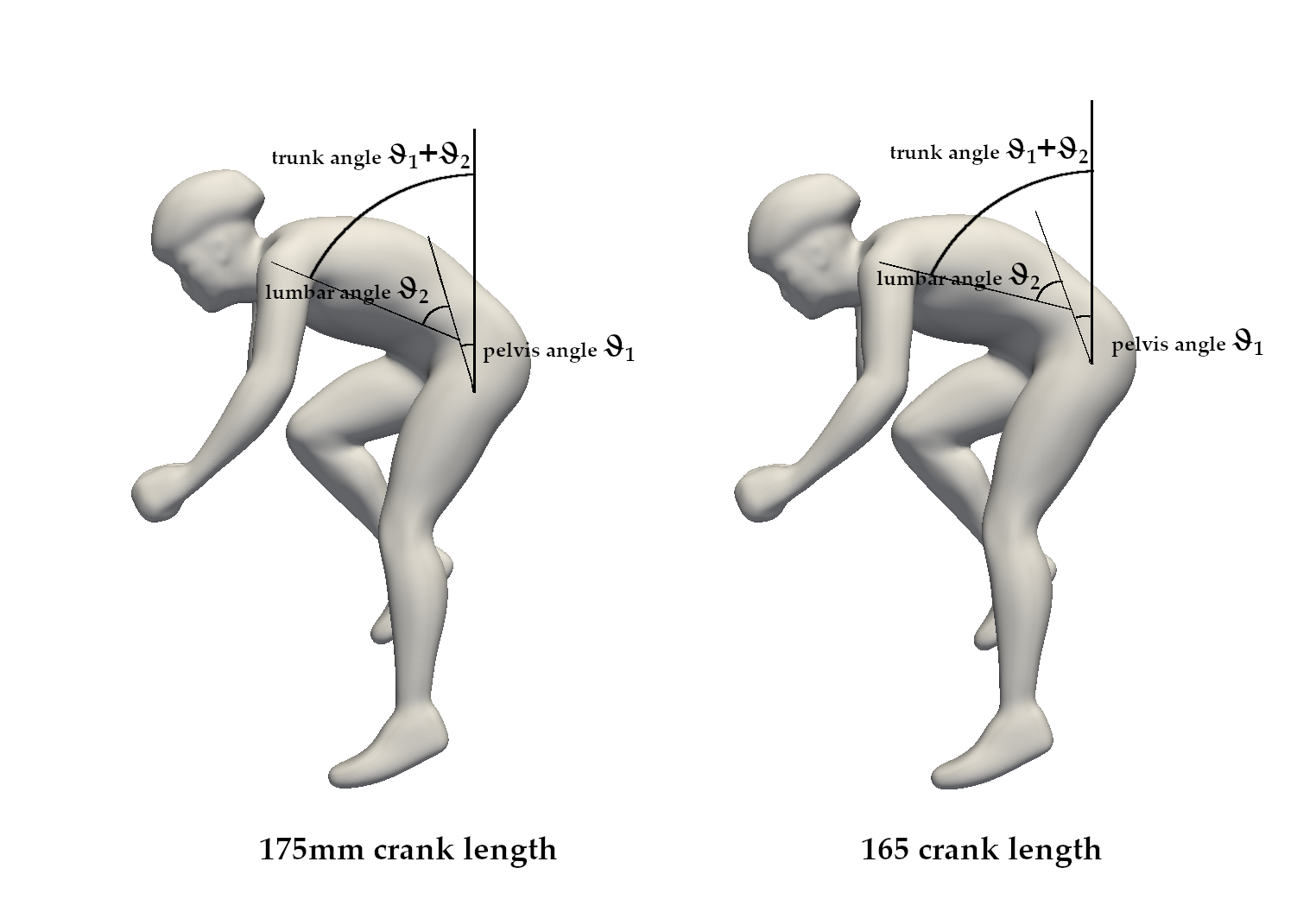

For the evaluation of trunk posture, sagittal plane tilting of the pelvis relative to the global coordinate system was quantified as anterior pelvic tilting and trunk angle was defined as the angle between the vertical and a line connecting the greater trochanter and the glenohumeral joint (Figure 1).

Data from all cyclists was averaged over 10 consecutive pedal similar strokes in the last 10 minutes of the 30 minutes laboratory testing. The first aspect that was analyzed was the trunk posture change: all cyclists achieved a lower trunk posture and the anterior pelvis tilt was the one that showed the most significant change in 4 cyclists (2.2 degrees average) with respect to the lumbar angle (1,6 degrees average), while the other 3 cyclists had a slight opposite tendency with a change of 1.8 degrees of the pelvis and 2.3 degrees of the lumbar angle (Table 2).

| Groups | Pelvic tilt (º) | Lumbar angle (º) | Trunk angle (º) |

| Group

1 (cyclist 1, cyclist 2, cyclist 5, cyclist 7) |

9.1 | 60.7 | 69.8 |

| 11.3 | 62.3 | 75.2 | |

|

Group

2 (cyclist 3, cyclist 4, cyclist 6) |

9.8 | 59.7 | 69.5 |

| 11.6 | 62 | 73.6 |

All cyclists increased their cadence and, on average, they pedaled at 87% of the cadence needed to reproduce the same pedal speed of the previous session. To analyze the changes in the velocities of the joints it is necessary to look at how the angles of the joints and if their range of motion has changed: the joint angular excursion determines the moment arm length and consequently the moments that the muscles that act on the joint can generate. The range of motion influences directly the velocity of the acting /involved monoarticular muscle, which influences their efficiency in delivering force. Due to the shorter crank length, there will be a tendency to reduce the range of motion of the joints and for this reason decrease their angular velocity on average, so that the joint velocities will not have the same characteristics of a standard (with the same crank length) faster pedaling rates. The hip range of motion was translated to higher maximal and minimal values due the increased inclination of the pelvis and the excursion was on average lower. The knee and ankle joint excursion was almost uniformly lower, as the angle at TDC was less flexed for the knee and less dorsiflexed for the ankle, while at 180 degrees the two joint angles were similar in the two tested situations due to the positioning of the cyclist that was meant to kept as close as possible, in the lower crank position, the inclination of the three segments of the lower limbs (thigh, shank and foot).

| Cyclist | Min hip angle(º) | Max hip angle (º) | Excursion hip angle (º) | Min knee angle (º) | Max knee angle (º) | Excursion knee angle (º) | Min ankle angle (º) | Max ankle angle (º) | Excursion ankle angle (º) |

| Cyclist 1 | 83.84 | 28.82 | 55.02 | 113.05 | 32.18 | 80.87 | -23.12 | 1.55 | 24.67 |

| 82.02 | 28.91 | 53.11 | 110.95 | 32.77 | 78.18 | -22.58 | 1.13 | 23.71 | |

| Cyclist 2 | 82.76 | 29.85 | 52.91 | 112.7 | 30.42 | 82.28 | -24.96 | -1.83 | 23.13 |

| 80.11 | 32.81 | 47.30 | 108.23 | 30.37 | 77.86 | -31.56 | -3.23 | 28.33 | |

| Cyclist 3 | 82.34 | 29.39 | 52.95 | 113.59 | 31.55 | 82.04 | -29.06 | -2.96 | 26.1 |

| 81.02 | 30.01 | 51.01 | 108.88 | 30.39 | 78.49 | -26.39 | -8.13 | 18.26 | |

| Cyclist 4 | 88.84 | 31.35 | 57.49 | 112.36 | 28.12 | 84.24 | -28.12 | -7.33 | 20.79 |

| 86.34 | 32.01 | 54.33 | 110.00 | 28.31 | 81.69 | -20.22 | 0.13 | 20.35 | |

| Cyclist 5 | 84.38 | 31.66 | 52.72 | 110.95 | 29.57 | 81.38 | -23.72 | 2.83 | 26.55 |

| 87.39 | 28.55 | 58.84 | 108.52 | 29.91 | 78.61 | -25.56 | 3.87 | 29.43 | |

| Cyclist 6 | 81.04 | 29.95 | 51.09 | 112.58 | 28.45 | 84.13 | -23.31 | 4.43 | 27.74 |

| 79.9 | 32.01 | 47.89 | 109.55 | 26.34 | 82.21 | -22.56 | 5.09 | 27.65 | |

| Cyclist 7 | 82.34 | 29.95 | 52.29 | 112.55 | 28.19 | 84.36 | -23.85 | 2.03 | 25.88 |

| 82.01 | 31.01 | 51.01 | 109.12 | 27.79 | 81.33 | -24.56 | 1.13 | 25.69 | |

| Average (SD) | 83.64 (2.34) | 30.13 (0.94) | 53.51 (1.94) | 112.54 (0.75) | 29.78 (1.53) | 82.75 (1.35) | -25.16 (2.24) | -0.19 (3.7) | 24.98 (2.18) |

| 82.68 (2.76) | 30.76 (1.52) | 51.92 (3.67) | 109.32 (0.86) | 29.55 (1.74) | 79.76 (1.74) | -24.77 (3.37) | -0.01 (4.14) | 24.77 (3.90) |

As already outlined, the increase of the pedaling rate combined with a lower excursion of the joints could partially balance one another in their opposite influence on the joint angular velocities (Table 4): in average cyclists had lower joint excursions for all joints and, apart for the ankle joint, their angular velocity was increased just sligthly.

| Joint velocities | 175 mm (or 172.5) crank length | 165 mm crank length | Comparison | |

| Hip | frequency | 90 | 93.88 (+3.1%) | > |

| excursion (º) | 53.51 | 51.92 (-3.1%) | < | |

| angular joint velocity (rad/s) | 2.80 | 2.83 (+1.1%) | = | |

| Knee | frequency | 90 | 93.88 (+3.1%) | > |

| excursion (º) | 82.75 | 79.76 (-3.8%) | ≪ | |

| angular joint velocity (rad/s) | 4.33 | 4.35 (+1.1%) | = | |

| Ankle | frequency | 90 | 93.88 (+4.3%) | > |

| excursion (º) | 24.98 | 24.77 (-0.9%) | = | |

| angular joint velocity (rad/s) | 1.31 | 1.35 (+3.0%) | > |

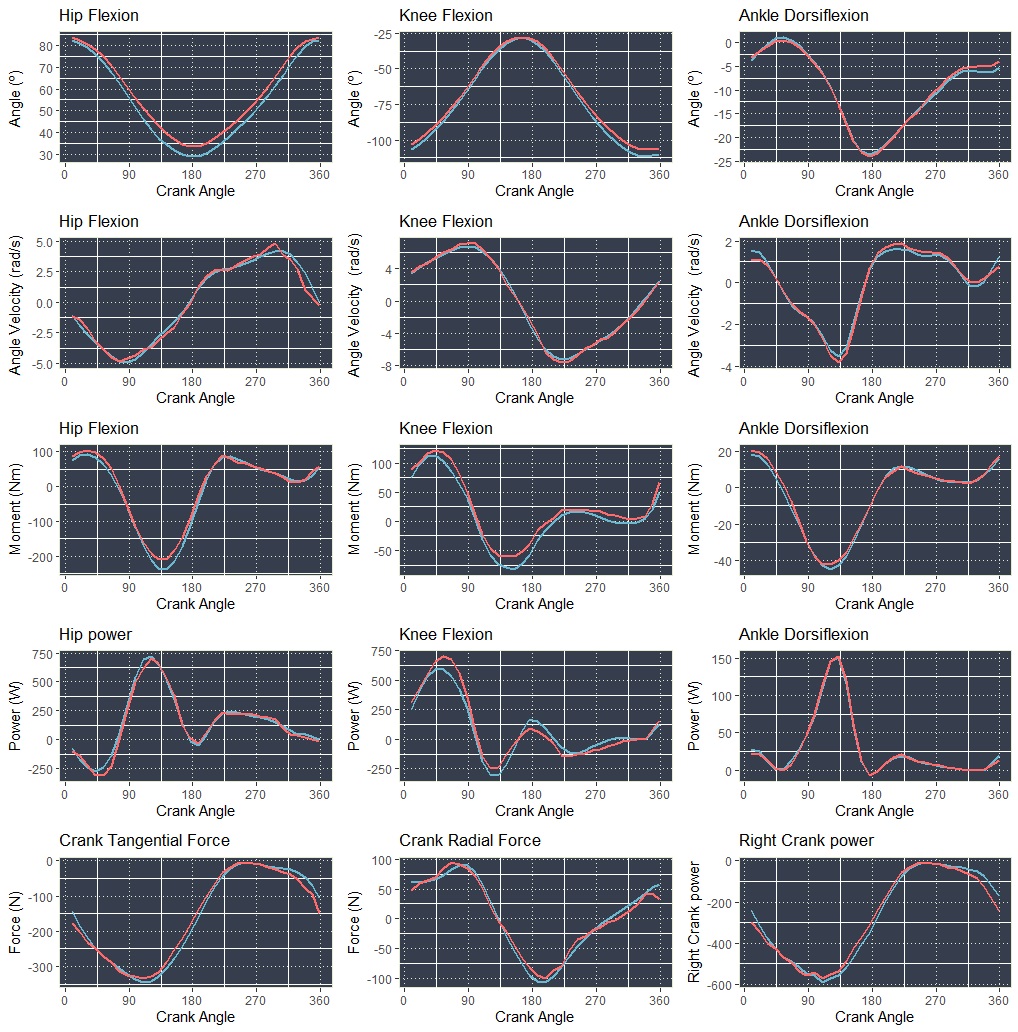

Forces summary data for each cyclist is reported in Table 5. Tangential positive force profiles were slightly changed in all cyclists with a tendency in anticipating the positive peak with respect to the crank revolution. Negative tangential forces were present in the first testing session in only 3 cyclists and they did not elicit a relevant change in the second session force curves. The most relevant change (which was consistently across 5 cyclists) was an increase of the propulsion forces (tangential forces) at the top zone of the pedal revolution (-20º, 20º) which was counterbalanced by a decrease in the propulsive force in the downstroke with a relevant reduction of the peak tangential forces. This result seems to have notable causes, which we searched for in the second phase of our analysis and as a consequence a lower peak force for some muscles, which can help lower fatigue and metabolic cost. Such a change in coordination may allow for less power fluctuation across the crank cycle.

| Cyclist | Positive and negative tangential forces | ||||||

| Max tangential force | Positive tangential force (%) | Negative tangential forces | Normalized negative work | ||||

| (N) | Crank Angle (º) | Median forces (N) | Excursion (º) | Average negative forces (N) | Excursion (º) | (%) | |

| Cyclist 1 | 342.0 | 109.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 322.0 | 108.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| Cyclist 2 | 375.0 | 103.0 | 267.8 | 325.0 | 18.0 | 35.0 | 99.3 |

| 347.0 | 102.0 | 269.5 | 322.0 | 10.0 | 38.0 | 99.6 | |

| Cyclist 3 | 365.0 | 116.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 342.0 | 110.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| Cyclist 4 | 349.0 | 105.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 348.0 | 106.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| Cyclist 5 | 375.0 | 103.0 | 271.4 | 322.0 | 26.0 | 38.0 | 98.9 |

| 352.0 | 101.0 | 265.9 | 328.0 | 25.0 | 32.0 | 99.1 | |

| Cyclist 6 | 369.0 | 96.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 346.0 | 94.0 | 245.7 | 352.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 99.9 | |

| Cyclist 7 | 345.0 | 102.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 323.0 | 100.0 | 240.0 | 360.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| Average (SD) |

360.0 (13.2) | 104.9 (5.8) | 248.5 (13.4) | 349.6 (16.5) | 6.3 (10.2) |

10.4 (16.5) | 99.7 (0.4) |

|

340.0 (11.4) | 103.0 (5.0) | 248.7 (12.2) | 348.9 (15.4) | 6.3 (8.7) |

11.1 (15.4) | 99.8 (0.3) | |

The tested number of cyclists was too low to consider it a valuable basis for a statistical analysis and we preferred to gather information from the data in a analytical way. We have reported in the tables the summary values of each cyclist in the two conditions, while the detailed graphs refer to a representative cyclist, cyclist 7, who changed the crank from 175 mm to 165mm and therefore the changes are visually more evident. Significant between-cyclist differences were seen in the shape of the forces curves (normal and tangential components) as a peculiar style of the cyclist, which constituted another reason to choose a single cyclist for our next charts and further discussion.

Joint net moments, as a consequence of the alterations in the crank forces, show some relevant modifications. The hip and the knee were the most affected, while the ankle showed less than 1.5% change all along the crank cycle. The hip joint showed a slight increase at the initial part of the crank revolution while extending and then had the largest change during the central part of the downstroke (main power phase) where its peak value was 5.8% lower. The knee joint moment was the most affected by the shorter crank , which resulted in a relevant increase (7.2%) of its peak extension moment in the first sector of the crank revolution and then a decrease of its flexion moment in the second half of the downstroke as a consequence of the reduced peak force applied at the crank during the maximal power phase (the lower tangential forces applies as shown in Figure 2.

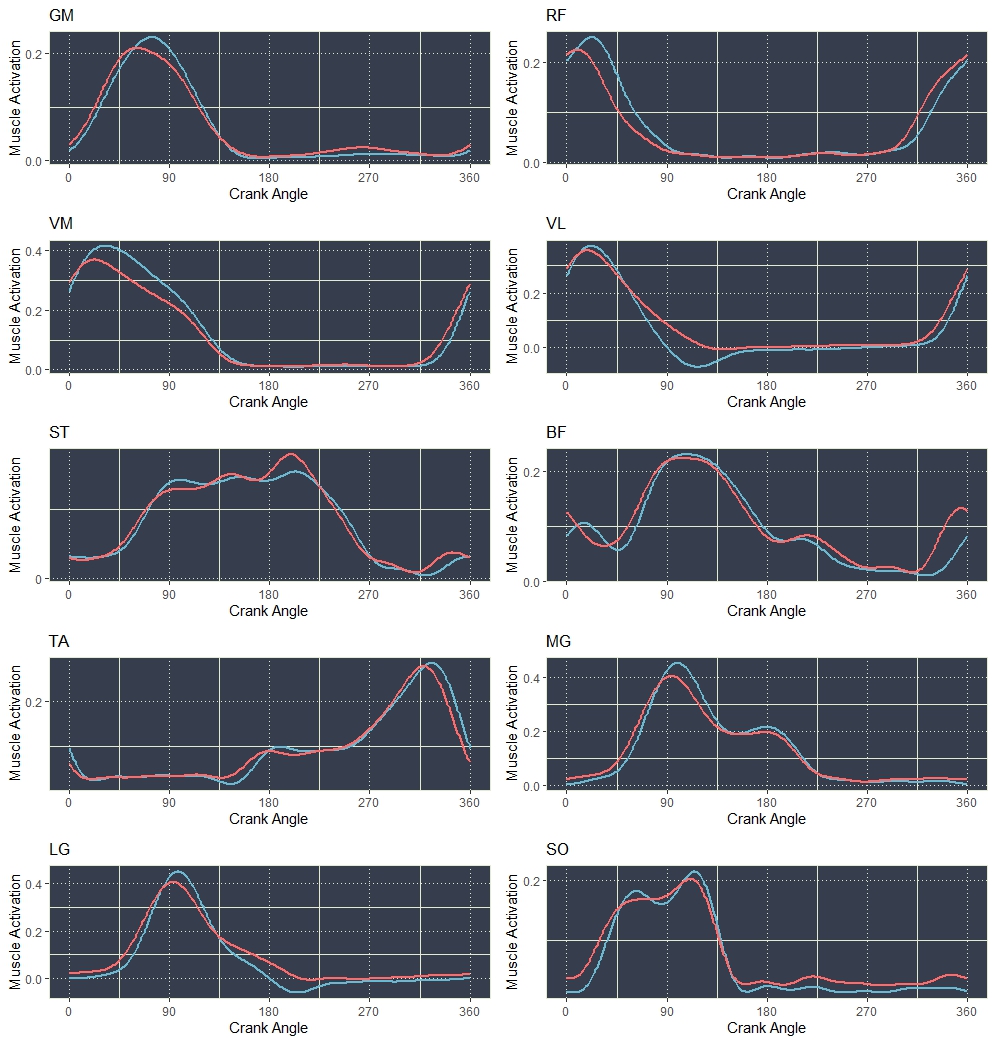

To evaluate how the dynamics of the three joints had changed we analyzed muscle dynamics. The computed muscle control (CMC) algorithm of openSim was used to compute 41 individual muscle excitations per limb that generated motion that tracked the experimental kinematics when the pedal reaction forces are applied. Muscles parameters, which were initially scaled by the openSim scaling tool, were moreover calibrated to the individual cyclist maximal force. The cyclist underwent a supplementary laboratory testing during which he was asked to pedal, after 20 minutes warm-up) at his maximal power for 1 minute. Then most muscles maximal force were incremented and their upper limit was set in order to generate the moments on the joints to deliver maximal power.

Both hip extensors, knee flexors and ankle plantar-flexors are fundamental in the central part of the downstroke where the maximal torque on the crank is generated (65o to 125o on the crank cycle). The lower peak values in the crank forces profiles with the 165mm crank setup is reflected in a lower activation level of the hip extensors (were the Gluteus maximus is shown in figure 3 as the main representative of this group) and lower values of the medial gastrocnemius and lateral gastrocnemius, which are used in the plantar flexion the ankle and, in a minor extent, in the flexion of the knee.

The length and velocity of muscle fibers can have a large effect on muscle force generation and the changes in the cyclist position and joint kinematics altered their characteristics along the crank cycle. In the aerodynamic position with the shorter crank, the length of the monoarticular muscles at the hip was maintain in most of the crank cycle as the increased anterior pelvic tilt counterbalances the more extended leg.

The knee muscles are influenced by a minor excursion which allows them to work in a closer to optimal fiber length. The monoarticular flexor of the knee (bicipeds femoralis short head) and the knee extensors Vastus Lateralis, Vastus Intermedius and the Vastus Medialis operated in a smaller range of their length, which was more closely centered on their optimal length (normalized muscle length = 1).

Vastus Medialis and Vastus Lateralis were both slightly lower activated managing to obtain the same force output as the long crank trial due to a more favorable muscle length (Figure 4 - top) and, to a minor extent, a lower shortening muscle velocity. The knee joint moment resulted in 6.8% increased for the Vastus Medialis and 4.7% increased for the Vastus Lateralis due to the same force applied and a longer muscle arm (Figure 4 - bottom).

The ankle joint, which did not show relevant joint range of motion and angular velocity changes, was activated by the gatrendecmius and the soleus in the downstroke as plantarflexors and tibialis anterior in the upstroke and transition top zone. In this part the TA showed and increased activation in the 165mm crank setup, to transmit the increased exercion of the knee flexors.

We investigated how varying crank length and torso inclination affect joint kinematics and dynamics, and muscle activation patterns during cycling in order to better understand how a different bycicle setup with a shorter cranks might mitigate the biomechanical challenges associated with an aerodynamic posture. From our results, it seems plausible that at least some high-level cyclists can manage to improve their aerodynamic position and have some beneficial effect from having a reduced range of motion, in particular in the TDC sector of the crank revolution (transition zone from upstroke to downstroke) where the knee joint encounters favorable angles (a lower maximal flexion at the joint) for the muscles acting on it.